In the shadow of Jevons

When efficiency brings environmental destruction

What if our cars used less gaz? And our telephones less electricity? What if we replaced letters with e-mails? Would that help solve the ecological crisis? Certainly not, says a book that’s almost two centuries old.

Jevons paradox

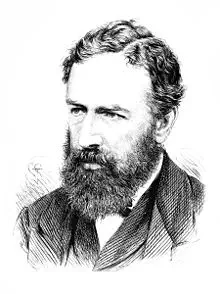

In 1865, Williams Stanley Jevons published a book entitled “The Coal Question”. In it, Jevons makes the following observation: in England, the overall consumption of coal increased enormously after the invention of new, more efficient steam engines. Thus, a technological innovation reduced the consumption of a resource on an individual scale, but increased the overall consumption of that resource in society.

This contradiction is known as Jevons’ paradox. It’s explained by the fact that increasing the efficiency of a technology reduces its cost of use, which in turn increases its utilization and overall resource consumption. 150 years on, this paradox continues to hang over us. After all, isn’t that new smartphone that consumes less electricity tempting, with its beautiful “sustainable development” logo? And that new car that uses less gaz, with its “good for the planet” label?

Efficiency, an often misleading marketing tactic

As you may have gathered by now, Jevons’ paradox fits in well with our consumer society. For example, it has been observed in the automobile sector for some time now. Cars that consume less mean cars that are cheaper to drive on a daily basis, and therefore an incentive to drive more. The same applies to aircrafts. In 50 years, aircraft fuel consumption per kilometer has fallen by 70%. But at the same time, the price of flights has fallen, and the number of flights has soared. As a result, global GHG emissions from aviation have risen by 400% over the same period.

If we were to continue the list, it would be long: from intensive agriculture, which has increased our surface area used for farming , to e-mails, which have increased - not decreased - global paper consumption , Jevons’ paradox is illustrated everywhere in our societies. It calls into question the seductive proposition that we can save the planet by innovating a little more, and buying the latest version of a popular product.

A social solution rather than a technological one ?

Fortunately for us, Jevons’ paradox is not inevitable. It depends on many economic conditions that are not always respected, and which can be avoided. For example, a well-placed tax can avoid its appearance by preventing a reduction in the cost of use.

Despite this, Jevons’ paradox suggests that technological innovation will not be the solution to our environmental problems. Our societies will have to rethink the value we place on nature, and how to limit or reverse our growth while ensuring our well-being. Indeed, it is only by placing limits on growth that innovation can truly help our environment.