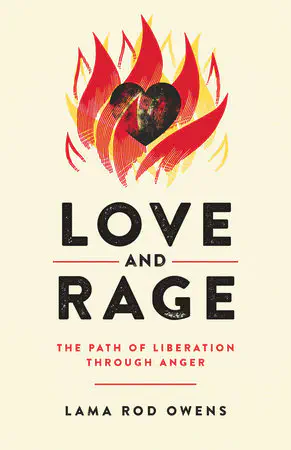

Book review : Love and Rage, The Path of Liberation through Anger by Lama Rod Owens

In world that always feels unfair, acceptation is the key to changing it.

Recommendation : ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Love and Rage is a call to accepting and appreciating our anger, rather than distrust and avoid it. But why should we do such a thing, when anger is precisely the source of so many of our problems ? Only a true buddhist could sit through this paradox. But luckily, that’s what Rod Owens did, and what he shares with us through this wonderful book.

While reading Love and Rage, I was sometimes confused to see Owens taking a lot of time delving into his own feelings and history, with a vocabulary that felt a bit mystical. Added to that, the text felt a bit unorganized, repeating its key points at very different locations of the book, and in different contexts. And yet, reading Love and Rage puts you in a kind of “flow” that is hard to describe. I think I’ve come to understand that this is often the style in which complex and paradoxical truths, like the ones touched upon by buddhism or zen, are best understood : not with a scientific and organized writing, but as a lazy stroll through the streets of wisdom with a friend. Indeed, it would be possible to synthesize many of the main ideas of Love and Rage in one simple sentence; but we wouldn’t necessarily accept it or understand it better.

Still, I’ll try to summarize some of the most interesting point of the book here, with the caveat that they will be best understood by reading the whole thing. And I definitely recommend it, as it gives great insights on love, rage, but also on how they interact with systemic oppression.

The hidden truth of anger

One of the key ideas of Love and Rage is that anger always comes from another emotion. This means that anger never comes out of nowhere - except in some very rare medical cases. In particular, anger comes from things that hurt us, or from desires that were not fulfilled.

In those situations, anger comes to save the day (or so it thinks). It arise with the promise of hurting or destroying the thing that hurt us, which will surely make the hurt stop. As such, it is easy to see why anger is there as a pretty logical evolutionary mechanism. You hurt me, I hurt you; then, you’ll surely stop hurting me in the future.

, author of Love and Rage](/post/love_and_rage_owens_2020/lama_rod_owens_hu5fea430c6379f85f65ad6852ec34aeb6_590656_55f25aa029f52cbfc39c33da6f5a3377.webp)

But this is not really the case, because of two important facts that anger makes us forget : the first is that it is not always possible to hurt the things that hurt us. They might be inaccessible, or too powerful for us, or hurting them will take a long, long time. This is often the case when dealing with systems of injustice or oppression : you can’t hurt or destroy a system that easily. And even if you do, you’ll not necessarily see satisfying results. The second, Owens explains, is that even if we manage to hurt what hurt us, it will not necessarily heal the hurt that has been done in the first place - or not even prevent future hurt. If someone bumps into you and hurts you, pushing them hard will not heal the pain you’re feeling, and might make them more prone to escalate the situation, causing even more hurt.

Those two realities - that we can’t always hurt back, and that it doesn’t solve anything - can easily create a vicious circle of anger and pain. This is because anger is good at hiding what caused it, and is also good at reinforcing itself. Hence, we’re hurt, and this makes us angry; anger makes us look away from the hurt, and focuses us on hurting back. Hurting back doesn’t heal us, and we get hurt even more. This means that we get angry even more, creating a positive feedback that can lead us to terrible situations.

From the point of view of Owens, understanding this reality of anger is the first step to a form a healing. This healing, in turn, is essential for us today, because we are constantly hurt by an unfair reality. Especially if we are part of an oppressed minority, if we are an activist, or if we are a member of the oppressive majority that suffers the price of our status.

Healing from anger with love

Healing anything through love has always sounded to me like a very superficial sentence; the kind that you would see in a Facebook post or on a bumper sticker at the back of a car. The kind of things that people say to sound wise, but that they do not do, as it does not contain anything of substance. And while that might be right in some cases, there is an important truth in this sentence that Love and Rage made me humbly realize.

What is love ? - Baby don’t hurt me…no more, says the song. And it’s pretty spot-on for the second key idea of Love and Rage. According to Owens, it’s important to understand what love actually is to start healing. And what love actually is, according to him, is really acceptation. Loving somebody, or something, means accepting them. In turn, accepting them does not mean justifying them, or thinking them good. It means that we take the time to let them be, to listen to them, and to consider them.

](/post/love_and_rage_owens_2020/simran-sood-qL0t5zNGFVQ-unsplash_hu1d962a6d9214d9038a21410d763f35ba_1135819_102d3f5daf5166f230eac981f5e23bff.webp)

As such, Owen uses love in a very “buddhist” sense (which makes sense, being a buddhist himself). But this, in turn, helps us understand the practical solution that he proposes to heal anger; or rather, to have the right relationship with it. To break the vicious circle of anger, to make sure that it doesn’t take control of us and to see what it hides, the first step is to accept it. And accepting it means listening to it; which means to spend time focusing on how it feels like.

For anybody that have known anger, it is easy to understand how un-intuitive that is. When we’re angry, we tend to be completely focused on the intents that anger arise in us. But none of the intent is to actually take the time to breath and feel what we’re feeling. It’s quite the opposite. We don’t want to look at anger, because looking at anger means looking at the pain; and anger is precisely here to make us forget the pain. But for anybody that has heard or practiced what we now call mindfulness, it makes complete sense.

As Owens puts it very well into words, this is really the action of putting space around anger. We still feel angry; but by practicing this form of love, of acceptation (and pratically speaking, of mindfulness), we start feeling other things too. We see details about the situation that anger - during what is called the emotional refractory period - makes us forget. And one of these things can be the fact that we need to get away from the situation, until we’re not angry anymore.

Then, the rest is more or less simple : once we can sit with anger and really feel it, we can also discover the cause that made it appear. And this, in turn, can allow us to really do what we need to do to heal the hurt, or satisfy our real needs (and not just the need to hurt others created by anger). In practice, Owens proposes meditation exercise to help with this. From my own experience with meditation (even if I am not buddhist), I can only agree. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy exercises can also be of help. But in the end, this might be much more important than what we might think : because anger does tie with many systems of oppression or injustice that we may deal with in our daily lives.

The path of liberation through anger

“They’re hysterical”. “They’re terrorists”. “They’re crazy”. “They’re violent”. We often hear those words used to describe not only activists, but also oppressed minorities as soon as they start complaining, protesting or acting against oppression or injustice. Indeed, Owens spends a large amount of his book delving into his own history as a black and queer man to show how much his own anger was used against him by a society that didn’t want him to be black and didn’t want him to be queer.

This is how the subject of anger in Love and Rage ultimately links with something even bigger than our personal mental health. Anger and pain are not just about us, because anger and pain are used to manipulate us, to keep us silent, and to keep us looking undesirable by unjust structures or systems. They can also be used to push us to hurt others when we are a part of those systems. But it can even be used by individuals just looking to hurt you, out of any particular system of oppression : sometimes, people are just mean.

As such, another key point of Love and Rage is that self-care is, in itself, a political act. Taking care of yourself, of your anger, and of what it hides is radical in a world that wants to hurt you. It’s even revolutionary, according to Owens. Indeed, if you live in a racist world that wants to keeps white people on the top of the power structure, then thriving and being happy in this world as a black person goes against this system.

](/post/love_and_rage_owens_2020/gayatri-malhotra-amfnvOvlAVw-unsplash_hu59e5d5b16f436db4e58d1ed32c4e3694_2468362_8f655c0ed64ed591e7e12b8459d292e8.webp)

But it goes further than just being symbolic : being happy keeps you in control, and keeps you from making many mistakes when fighting this system. It keeps you running on the long-run; which is important, as figthing such systems takes a lot of time and efforts. And don’t worry about losing your drive to fight what you see as injustices; anger will always be there, says Owens. But if you accept it, if you love it, you will not be controlled by it. You will have the right relationship with it as an activist; one that might lead you and others, one day, to a path of personal and systemic liberation.

From my own point of view, the whole thing goes beyond just the subject of anger. I’d say that in general, if you want to change anything - a system, a situation, a person or even an object -, you’ll need to accept it first. If you don’t, you just won’t see it right; you’ll be unable to see it from all perspectives, and from every angle. And then, you might end up wanting to change the wrong thing - or to change it in the wrong way. That’s why our current world where things become so complex, muddled, and yet so polarized, there seems to be no greater call than the call to take the time to listen to our anger more. Listen, but not obey.