Using Magic Harvest in practice

Authors: Clément Hardy1

Affiliations: 1Université du Québec en Outaouais (UQO)\

Getting on the field !¶

Here, we’re going to see the more technical details of using Magic Harvest :

- How to access the state of the LANDIS-II landscape in a Python or R script run with Magic Harvest ?

- How to edit the parameter files of Biomass Harvest to control harvesting ?

- Etc.

Looking at some example files for a simple simulation¶

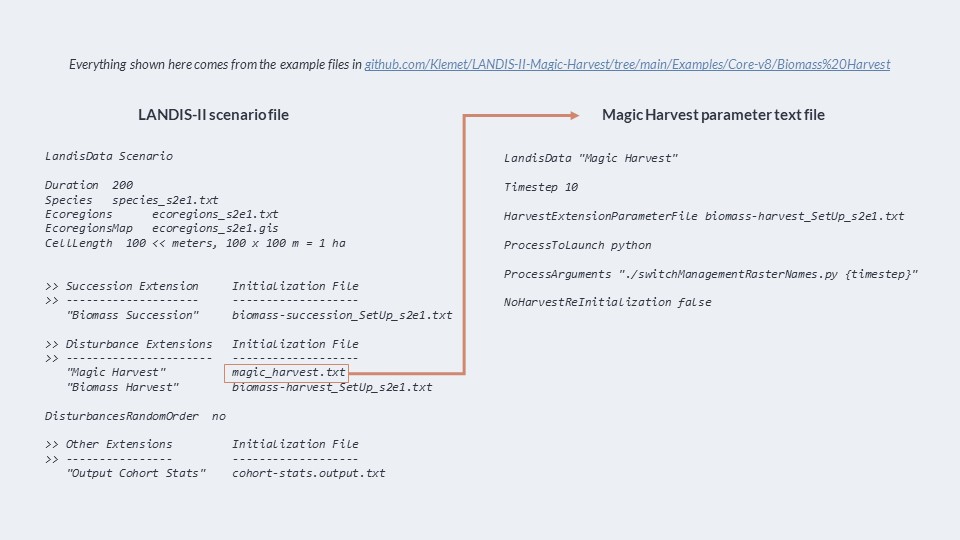

First of all, I’m going to show you some screenshots of a test scenario with Magic Harvest, with the test files that are on the repository of Magic Harvest. Just so that you have a visual idea of what it looks like in action.

Here is the scenario file that we have quickly seen before; as you see, Magic Harvest is indicated before B. Harvest, and the disturbance order is not random. The path points to the parameter text file of magic harvest. Here is the magic harvest parameter file, that we also have seen before; it’s very simple, and launches a Python script that simply switches the name of files to activate a different B. Harvest parameter text files.

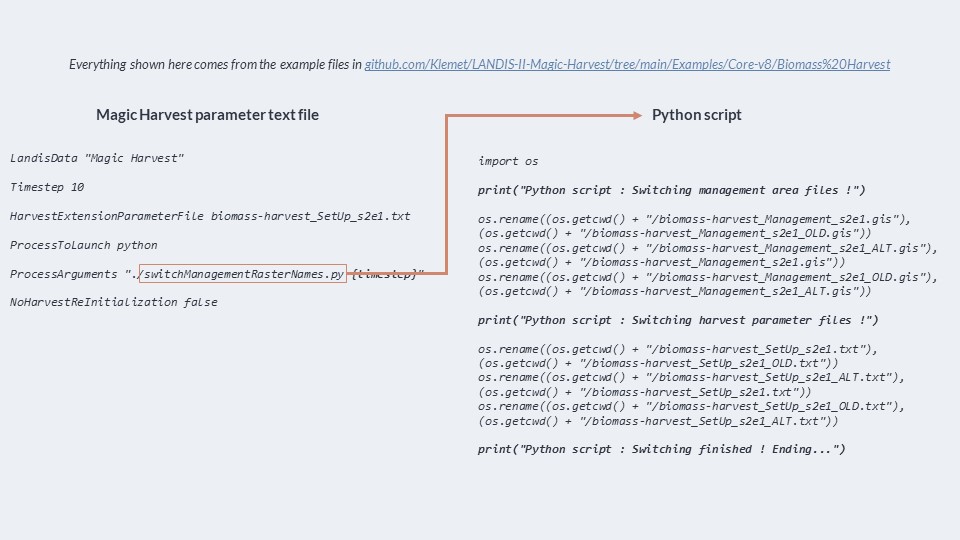

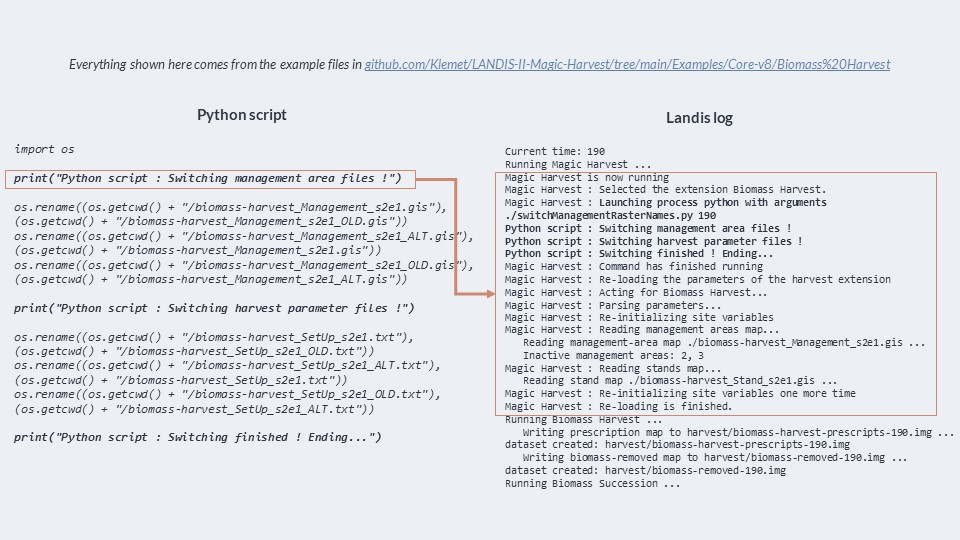

Here is the Python script launched by Magic Harvest everytime it runs. You see, it’s very simple. It simply renames files to switch between two sets of input files for B. Harvest. This is one of the simplest ways you can influence B. Harvest; you don’t even edit files, you just switch them.

And finally, here is the log of LANDIS-II when it is running. As you see, Magic Harvest writes in the log when it activates, when it’s done running, and when it re-loads the parameters of B. Harvest. We can even see the “print” statements that come from the Python script, and which indicate what the script is doing ! This is great for debugging. If B. Harvest is not installed or used in the simulation, Magic Harvest will warn you of it.

Taking a look at a Python script template¶

Now, I’m going to show you a “template” of a Python script I’ve been using in my PhD thesis and my post-doctoral work. This template reads the state of the landscape and other things, and then writes some files to give to B. Harvest. The rest (the management decisions based on the state of the landscape) are up to you to write. We’ll use this template as a base for the following exercice. You can download the full file here.

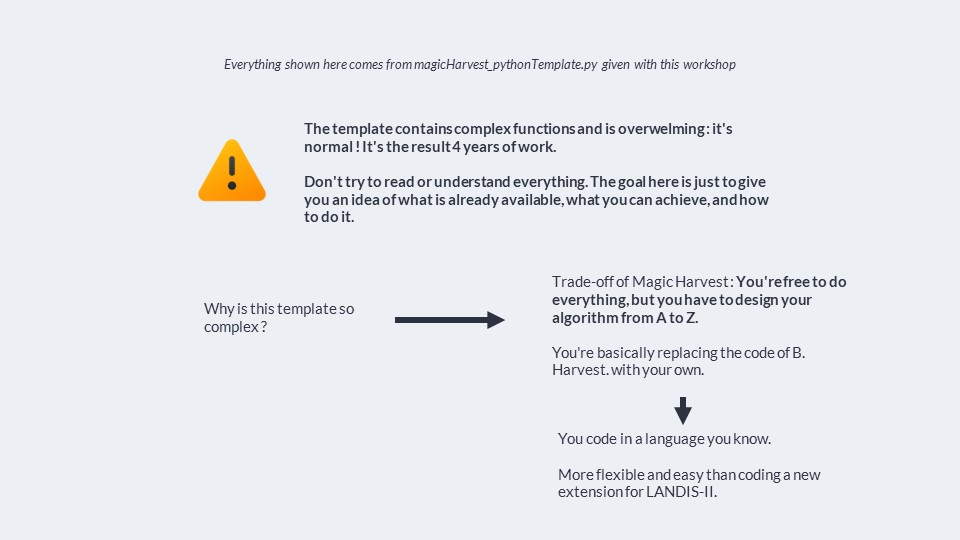

So first off, a warning : the template I’m about to show you is complex, even though I have removed any management decisions. You have to understand that I’ve spent years working on this script through two chapters of my thesis, and then my post-doc work. It’s full of functions made to do things quickly and in an optimized way. It’s also made to adapt to the pretty complex forms of management decision I’ve been making. So what I am about to show you is going to be overwelming. As such, I propose that you to not try to understand or read or remember everything. In the future, you might use this template for your own work; it is very heavily commented, and you will have the time to understand it piece by piece. Here, I simply want to give you a glimpse under the hood to show you what the engine can look like.

You might also feel like it’s not normal for this methodology to get this complicated; that Magic Harvest is nice, but that this is just too much work and complexity. It’s something I have often felt when working on this. But here, we are working a trade-off : Magic Harvest allow us to become free from the restrictive and pre-defined algorithms of LANDIS-II and do whatever we want, which is essential to our research; but the trade-off is that we have to write the code for that, and it gets complex; just like the code inside LANDIS-II is. It’s just that usually, we don’t touch the LANDIS-II code as users. Here, we have to code everything. That’s the trade-off.

We could, of course, code a whole new harvest extension for LANDIS-II instead of using a script like this; but this become restrictive again because you have to deal with the complex building process of extensions in the C# langage that LANDIS-II uses, you have to maintain them, and then future users become restricted by your algorithm. By using R or Python scripts, we can use simpler programming langages that most ecologist know to some degree, and we can share our scripts easily, and they can be re-used easily. So, no solution is perfect; but while this one is complex, it works realiably and gives us a high level of control.

So, ready ? Let’s dig in.

Defining functions for everything¶

The beginning of this template is simply a section where a lot of functions are defined so that we can use them afterwards. I really advise you define functions like this. It makes the rest of the code much clearer. In Python, it is really easy to describe each function you’re writting, in particular its inputs and outputs, via a “docstring”, a string of text that documents the function. Modern text editors allow you to write it quickly. AI can write it for you too.

Here is an example in the script :

def readingStandsCoordinates(standRasterDataAll, disableTQDM):

'''Reads the stands map to get the coordinates of each pixel in a stand.

Returns a dictionnary giving the coordinates for each pixel for a given

stand ID. Locations are in (row, column) tuple format, as necessary to

access a value in a numpy array made from a raster by Rasterio.

standRasterDataAll must be a numpy array contained the data from your raster map.'''

print("Reading stands coordinates...")

standCoordinatesDict = dict()

uniqueAllStandsID = np.unique(standRasterDataAll).tolist()

# id 0 for stands = no forests

uniqueAllStandsID.remove(0)

for standID in tqdm(uniqueAllStandsID, disable = disableTQDM):

# print(standID)

standCoordinatesDict[standID] = list()

for x in tqdm(range(standRasterDataAll.shape[0]), disable = disableTQDM):

for y in range(standRasterDataAll.shape[1]):

standID = standRasterDataAll[(x, y)]

if standID != 0:

standCoordinatesDict[standID].append((x, y))

return(standCoordinatesDict)There’s a lot of functions here. The first ones are used to easily read and write raster map data. When we read raster map data, we put it in a “numpy” array - numpy being a very famous Python package that allows for extremely efficient vectorial, matricial, or generally multi-dimensional array computation. So we put the values of the raster in a 2-dimensional array.

def getRasterData(path):

raster = gdal.Open(path)

rasterData = raster.GetRasterBand(1)

rasterData = rasterData.ReadAsArray()

return(np.array(rasterData))

def getRasterDataAsList(path):

return(getRasterData(path).tolist())

def writeNewRasterData(rasterDataArray, pathOfTemplateRaster, pathOfOutput):

# Saves a raster in int16 with a nodata value of 0

# Inspired from https://gis.stackexchange.com/questions/164853/reading-modifying-and-writing-a-geotiff-with-gdal-in-python

# Loading template raster

template = gdal.Open(pathOfTemplateRaster)

driver = gdal.GetDriverByName("GTiff")

[rows, cols] = template.GetRasterBand(1).ReadAsArray().shape

outputRaster = driver.Create(pathOfOutput, cols, rows, 1, gdal.GDT_Int16)

outputRaster.SetGeoTransform(template.GetGeoTransform())##sets same geotransform as input

outputRaster.SetProjection(template.GetProjection())##sets same projection as input

outputRaster.GetRasterBand(1).WriteArray(rasterDataArray)

outputRaster.GetRasterBand(1).SetNoDataValue(0)##if you want these values transparent

outputRaster.FlushCache() ##saves to disk!!

outputRaster = None

def writeNewRasterDataFloat32(rasterDataArray, pathOfTemplateRaster, pathOfOutput):

# Saves a raster in Float32 with a nodata value of 0.0

# Inspired from https://gis.stackexchange.com/questions/164853/reading-modifying-and-writing-a-geotiff-with-gdal-in-python

# Loading template raster

template = gdal.Open(pathOfTemplateRaster)

driver = gdal.GetDriverByName("GTiff")

[rows, cols] = template.GetRasterBand(1).ReadAsArray().shape

outputRaster = driver.Create(pathOfOutput, cols, rows, 1, gdal.GDT_Float32)

outputRaster.SetGeoTransform(template.GetGeoTransform())##sets same geotransform as input

outputRaster.SetProjection(template.GetProjection())##sets same projection as input

outputRaster.GetRasterBand(1).WriteArray(rasterDataArray)

outputRaster.GetRasterBand(1).SetNoDataValue(0)##if you want these values transparent

outputRaster.FlushCache() ##saves to disk!!

outputRaster = None

def writeExistingRasterData(rasterDataArray, pathOfRasterToEdit):

# Edits the data of an existing raster

rasterToEdit = gdal.Open(pathOfRasterToEdit, gdal.GF_Write)

rasterToEdit.GetRasterBand(1).WriteArray(rasterDataArray)

rasterToEdit.FlushCache() ##saves to disk!!

rasterToEdit = NoneThen, we have functions that read the state and structure of the landscape in LANDIS-II. To do that, we use input and output raster maps and files from LANDIS-II that will be in our simulation folder. Of course, when LANDIS-II runs, it has its own internal variables that contain the information on the landscape; but sadly, we cannot access these. These variables are contained in the RAM of your computer, and they are only accessible to the program. Since the script we are using is outside LANDIS-II - it’s run through Python, not LANDIS-II -, then we cannot access these internal variables of LANDIS-II.

But that’s fine, because we can use output extensions and some input files of LANDIS-II to get everything we need.

For example, to get the forest stands in the landscape, we can read the map of forest stands - the one that is usually given to B. Harvest.

def readingStandsCoordinates(standRasterDataAll, disableTQDM):

'''Reads the stands map to get the coordinates of each pixel in a stand.

Returns a dictionnary giving the coordinates for each pixel for a given

stand ID. Locations are in (row, column) tuple format, as necessary to

access a value in a numpy array made from a raster by Rasterio.

standRasterDataAll must be a numpy array contained the data from your raster map.'''

print("Reading stands coordinates...")

standCoordinatesDict = dict()

uniqueAllStandsID = np.unique(standRasterDataAll).tolist()

# id 0 for stands = no forests

uniqueAllStandsID.remove(0)

for standID in tqdm(uniqueAllStandsID, disable = disableTQDM):

# print(standID)

standCoordinatesDict[standID] = list()

for x in tqdm(range(standRasterDataAll.shape[0]), disable = disableTQDM):

for y in range(standRasterDataAll.shape[1]):

standID = standRasterDataAll[(x, y)]

if standID != 0:

standCoordinatesDict[standID].append((x, y))

return(standCoordinatesDict)For informations about the harvest prescriptions, we can simple “parse” the B. Harvest parameters text file. This is a bit more tricky, but the function is already there, and allows us to put all informations into a Python dictionnary. The dictionnaries of Python is an object that I love very much and use very often : it simply associate an object (e.g. a number, a sentence or a word, or any other object) with another. Here, by reading the harvest parameter text file, I created a big dictionnary that contains the information and rules about each prescription in there. This can be useful, for example, to estimate how much biomass these prescription will harvest in the cells. Making this estimation can be used to know if we have reached the targets we have for the current timestep.

def harvestParameterFileParser(path):

"""

Parses the biomass harvest parameter file at the given path.

Returns a dictionnary with the needed parameters.

WARNING : To read the harvest file properly, make sure to :

- Not use relative number of cohorts harvested for a given species, like

"1/2" or "1/3". Since this script is made to be used with biomass harvest,

use things like "11-999(50%)" to harvest half of the biomass of each cohort.

- Make sure the biomass percentages are not separated from their respective

age class, meaning write "11-999(50%)" rather than "11-999 (50%)"

"""

print("Reading harvest parameter file...")

dictToReturn = dict()

# WARNING : Here is the list of species I use. Replace it with your own species

# codes that you use in LANDIS-II !

speciesList = ["ABIE.BAL","ACER.RUB","ACER.SAH","BETU.ALL","BETU.PAP",

"FAGU.GRA","LARI.LAR","LARI.HYB","PICE.GLA","PICE.MAR",

"PICE.RUB","PINU.BAN","PINU.RES","PINU.STR","POPU.TRE",

"POPU.HYB","QUER.RUB","THUJ.SPP.ALL","TSUG.CAN"]

with open(path, 'r') as file:

prescriptionSelected = "none"

prescriptionID = 1 # We start at 1 because the ID is for the raster;

# 0 = not forest, 1 = forest not harvested, and then it's the prescriptions.

for line in file:

# print(line)

# We start by recording the lines if we're reading a prescription

if prescriptionSelected != "none" and "Prescription " not in line:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["FullString"].append(line)

if ">>-------------" in line:

prescriptionSelected = "none"

# We get the timestep used by the extension

if "Timestep" in line:

timestepLength = int(splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)[1])

# If we find a new prescription, we initialize everything needed

if "Prescription " in line:

prescriptionSelected = line[len("Prescription "):-1] #-1 removes the \n character at the end of each line

if prescriptionSelected not in dictToReturn:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected] = dict()

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["Planting"] = "none"

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["RepeatMode"] = "none"

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["MaximumStandAge"] = 999

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["MinimumStandAge"] = 0

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["Commercial"] = True # Does it generate merchantable wood ?

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["FullString"] = [line] # We keep all the lines of the prescription to be able to copy it to make different plantings

prescriptionID += 1

dictToReturn["_MaxPrescriptionID"] = prescriptionID # Special counter used to create new planting prescriptions later

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["PrescriptionID"] = prescriptionID

singleRepeat = False

# Else, we register the parameters of the prescription

elif "MaximumAge" in line:

maximumAge = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)[1]

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["MaximumStandAge"] = int(maximumAge)

elif "MinimumAge" in line:

minimumAge = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)[1]

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["MinimumStandAge"] = int(minimumAge)

elif "SiteSelection" in line:

# The line contains 2 words + the two numerical values we want

# We remove everything we don't need to get the two values

splittedLine = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)

# print(splittedLine)

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["HarvestPropagation"] = [float(splittedLine[2]), float(splittedLine[3])]

elif "CohortsRemoved" in line and not singleRepeat:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"] = dict()

elif "Planting" in line:

plantingString = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)[1]

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["Planting"] = plantingString

elif "Commercial" in line and "FALSE" in line.upper():

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["Commercial"] = False

elif "SingleRepeat" in line:

singleRepeat = True

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"]["SingleRepeat"] = dict()

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["RepeatMode"] = "SingleRepeat"

repeatFrenquency = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)[1]

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["RepeatFrequency"] = int(repeatFrenquency)

elif "MultipleRepeat" in line:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["RepeatMode"] = "MultipleRepeat"

repeatFrenquency = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)[1]

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["RepeatFrequency"] = int(repeatFrenquency)

# If we get to the part about the cohort removed, it's a bit more tricky

# to register

# In particular, we will register the cohort removed in the case of a

# second pass (via SingleRepeat) in a different nested dictionnary

for species in speciesList:

if species in line and "Prescription " not in line and "Plant" not in line:

if not singleRepeat:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"][species] = dict()

else:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"]["SingleRepeat"][species] = dict()

# 3 cases :

# just ages (11-999)

# "All" keyword

# ages categories with biomass percent (11-999(90%))

# print(line)

if "/" in line: # Just in case their are relative cohort numbers in the file

raise ValueError("Do not use relative number of cohort harvested for a given species, like \"1/2\" or \"1/3\". Since this script is made to be used with biomass harvest, use things like \"11-999(50%)\" to harvest half of the biomass of each cohort.")

elif "All" in line or "all" in line:

if not singleRepeat:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"][species] = "All"

else:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"]["SingleRepeat"][species] = "All"

else: # If not all, we have to break appart the age categories

if not singleRepeat:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"][species] = list()

else:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"]["SingleRepeat"][species] = list()

splittedLine = splitLineAndRemoveTabsAndSpaces(line)

# print(splittedLine)

for ageCategory in splittedLine[1:]:

if "%" not in ageCategory:

splitAgeCategory = ageCategory.split("-")

# We add a list describing 1) min age of category 2) max age of category 3) % of biomass harvested

if not singleRepeat:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"][species].append([int(splitAgeCategory[0]), int(splitAgeCategory[1]), 100])

else:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"]["SingleRepeat"][species].append([int(splitAgeCategory[0]), int(splitAgeCategory[1]), 100])

else:

splitAgeCategory = ageCategory.replace("(", "-").replace("%)", "").split("-")

if not singleRepeat:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"][species].append([int(splitAgeCategory[0]), int(splitAgeCategory[1]), int(splitAgeCategory[2])])

else:

dictToReturn[prescriptionSelected]["CohortRemoved"]["SingleRepeat"][species].append([int(splitAgeCategory[0]), int(splitAgeCategory[1]), int(splitAgeCategory[2])])

if "HarvestImplementations" in line:

break

return(dictToReturn, timestepLength)Now, I’ve shown a function to read the stands, and one to read the B. Harvest parameter text file; but how do we get the vegetation data ? How do we know exactly what’s inside each cell in the landscape ? The age cohorts and their biomass ? Took me a while, but I found a great way. There is an output extension called Biomass Community Output that, at each time step, exports the entire landscape as a raster map + a communities csv file that is exactly like the ones that are used for the initial conditions of LANDIS-II. These files are very large, as they contain the most “raw” data that LANDIS-II can output. But with a bit of optimisation, Python can read them very quickly and put them into a dictionnary. In this dictionnary, we can access the age cohorts of each pixels of a given stand, their age, and their biomass. That gives us all of the information we will ever need to make management decisions.

def readCommunitiesComplete(communityCsvPath,

communityMapPath,

standCoordinatesDict,

disableTQDM):

"""

Reads the communities csv and raster map made by Output Biomass Community

to make a dictionnary containing the species and age cohorts for each

species and biomass for these cohorts for all of the pixels of a stand.

WARNING : the dictionnary doesn't contain entries for stands that have

no cohorts/no biomass, and no entries for species that are not in a stand

or cohorts that do not exist for a species. This saves on a lot of space,

but one got to check if the entries are there when using the dictionnary.

"""

# communityCsvPath = "./community-input-file-" + str(timestep) + ".csv"

# communityMapPath = "./output-community-" + str(timestep) + ".img"

print("Reading communities csv and map...")

# We only need the mapcode column from the csv from now.

communityCsv = pd.read_csv(communityCsvPath, usecols=['MapCode'])

communityMapCodeData = getRasterData(communityMapPath)

# We make the dictionnary of the amount of times a stand is associated

# to a mapcode

print("Creating mapcode community dictionnary...")

dictMapCodeStands = dict()

for uniqueMapCode in communityCsv["MapCode"].unique():

dictMapCodeStands[uniqueMapCode] = dict()

for standID in standCoordinatesDict.keys():

for pixel in standCoordinatesDict[standID]:

mapcode = communityMapCodeData[pixel]

# If the mapcode is not already in the dictionnary, it was not in

# the CSV; and if it's not in the CSV, it's because it's a mapcode

# associated to no cohorts at all(total biomass of 0)

if mapcode in dictMapCodeStands:

if standID not in dictMapCodeStands[mapcode]:

dictMapCodeStands[mapcode][standID] = 1

else:

dictMapCodeStands[mapcode][standID] += 1

# Now, we can read the CSV file and fill in a second dictionnary with the

# information for each stand

# To lighten it, we won't put stands that have no biomass

# (IMPORTANT FOR OTHER FUNCTIONS : have to check if stand is in dictionnary)

print("Creating stand community dictionnary...")

standCommunitiesDict = dict()

with open(communityCsvPath, 'r') as file:

reader = csv.reader(file)

headers = next(reader) # Read the header row

for row in tqdm(reader, total=len(communityCsv["MapCode"]), disable = disableTQDM):

# 0 is mapcode; 1 is species; 2 is cohort; 3 is biomass.

for standID in dictMapCodeStands[int(row[0])]:

if standID not in standCommunitiesDict:

standCommunitiesDict[standID] = dict()

standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]] = dict()

standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]][int(row[2])] = 0

# If species not indicated for this stand, we put it

elif row[1] not in standCommunitiesDict[standID]:

standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]] = dict()

standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]][int(row[2])] = 0

# If age cohort not indicated for this stand/species, we put it

elif int(row[2]) not in standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]]:

standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]][int(row[2])] = 0

# Finally, we enter the biomass for the stand/species/cohort

# If the stand has multiple pixel with this mapcode, we multiply

# the biomass with the number of pixels

# WARNING : Need to transform biomass from g/m2 to Mg/ha by dividing by 100

standCommunitiesDict[standID][row[1]][int(row[2])] += (int(row[3])/100)*dictMapCodeStands[int(row[0])][standID]

return(standCommunitiesDict)We then have other functions that can retrieve data we might need for management decisions. These functions used objects created by other functions that contain data about the vegetation. For example :

- Getting the biomass of a list of species we want to harvest in a stand (based on the vegetation data we have put in a dictionnary)

def GetBiomassInstand(standCompositionDict, standID, listOfSpecies):

"""Retrieves the total biomass in a stand for a list of species.

Returns a single biomass value."""

sumOfBiomass = 0

for species in listOfSpecies:

if species in standCompositionDict[standID]:

sumOfBiomass += sum(standCompositionDict[standID][species].values())

return(sumOfBiomass)- Reading the age of the stands (to see what stand are the oldest)

def readingStandsAges(standMapPath, maxAgeMapsFolderPath, timestep, timestepLength, disableTQDM):

'''Uses the stand maps and max age map to compute the mean age of each stand

(average of the age of the oldest cohorts in each pixels of the stand).

Returns a dictionnary associating an age to a stand ID.

The max age map is taken from the previous timestep to the current one.'''

print("Reading stands age...")

standData = getRasterData(standMapPath)

uniqueAllStandsID = np.unique(standData).tolist()

# id 0 for stands = no forests

uniqueAllStandsID.remove(0)

cohortMaxAgeData = getRasterData(maxAgeMapsFolderPath + "AGE-MAX-" + str(timestep - timestepLength) + ".img")

maxAgeDict = dict()

# Little trick to use the power of numpy below

# We make an array with the pixels we want the value of, and another

# with the values

pixelCoordinates = np.where(standData != 0)

standIDinPixelCoordinates = standData[pixelCoordinates]

for standID in tqdm(uniqueAllStandsID, disable = disableTQDM):

maxAgeDict[standID] = list()

# We get the data for the harvestable pixels

cohortMaxAgeInForestPixel = cohortMaxAgeData[pixelCoordinates]

# We fill the dictionnary with the different values of max cohort age for each

# pixels in a stand

for i in tqdm(range(0, len(pixelCoordinates[0])), disable = disableTQDM):

maxAgeDict[standIDinPixelCoordinates[i]].append(cohortMaxAgeInForestPixel[i])

# We make a dictionnary containing the mean max age for each stand

standAgeDict = dict()

for standID in tqdm(uniqueAllStandsID, disable = disableTQDM):

standAgeDict[standID] = statistics.mean(maxAgeDict[standID])

return(standAgeDict)- Reading the management unit associated to each stand (remember that we are going to give non-sensical management area maps to B. Harvest if we want to control its behaviour, but we might still want to use management areas in our Python script to make our management decisions)

def readingStandManagementUnit(standMapPath, managementUnitsMapPath, disableTQDM):

'''Assign a management unit (UA) code to each stand. This is not used to define

management units per say in our landscape, but rather to get the conversion

values from raw to net merchantable volume harvested, based on data from

the ministry of forest (the data changes by species and by management unit).

See coefficientRawToNetVolumes object for more info.'''

print("Reading stands management units (used for volume conversion)...")

standData = getRasterData(standMapPath)

uniqueAllStandsID = np.unique(standData).tolist()

# id 0 for stands = no forests

uniqueAllStandsID.remove(0)

managementUnitsMap = getRasterData(managementUnitsMapPath)

managementUnitDict = dict()

# Little trick to use the power of numpy below

# We make an array with the pixels we want the value of, and another

# with the values

pixelCoordinates = np.where(standData != 0)

standIDinPixelCoordinates = standData[pixelCoordinates]

for standID in tqdm(uniqueAllStandsID, disable = disableTQDM):

managementUnitDict[standID] = list()

# We get the data for the harvestable pixels

managementUnitInPixel = managementUnitsMap[pixelCoordinates]

# We fill the dictionnary with the different values of max cohort age for each

# pixels in a stand

for i in tqdm(range(0, len(pixelCoordinates[0])), disable = disableTQDM):

managementUnitDict[standIDinPixelCoordinates[i]].append(managementUnitInPixel[i])

# We make a dictionnary containing the mean max age for each stand

standManagementUnitDict = dict()

for standID in tqdm(uniqueAllStandsID, disable = disableTQDM):

standManagementUnitDict[standID] = Counter(managementUnitDict[standID]).most_common(1)[0][0]

return(standManagementUnitDict)- Writing in the raster map that we are going to create what pixels will be harvested with a given prescriptions

def harvestStands(managementMap, standsList, standCoordinatesDict, prescriptionID):

"""Edits the management map to indicate a list of stands as harvested with

a given prescription ID. Returns the modified management map."""

numberOfPixelsHarvested = 0

for standID in standsList:

for pixel in standCoordinatesDict[standID]:

managementMap[pixel] = prescriptionID

numberOfPixelsHarvested += 1

return(managementMap, numberOfPixelsHarvested)- A function to get what are the stands that are the neighbours of a stand if we want to propagate a cut accross several stand

def readingStandsNeighbors(standRasterDataAll,

standCoordinatesDict,

disableTQDM = True):

'''Reads the neighbors of each stand by looking at the surrounding

pixels of those of the stands, and getting their stand ID. Returns a dictionnary

with the list of neighbors's stand ID for each stand.'''

print("Reading stand neighbors...")

# Making a dictionnary which tells what stand is a neighbor of which one.

# We only need it for harvestable stands, since this is for the propagation

# of cuts.

standNeighboursDict = dict()

minXRange = range(standRasterDataAll.shape[0])[0]

maxXRange = range(standRasterDataAll.shape[0])[-1]

minYRange = range(standRasterDataAll.shape[1])[0]

maxYRange = range(standRasterDataAll.shape[1])[-1]

for standID in tqdm(standCoordinatesDict.keys(), disable = disableTQDM):

listOfNeighbouringStands = list()

for pixel in standCoordinatesDict[standID]:

listOfStandsAroundPixel = list()

# We look at the 8 neighbors of the pixel, if not out of range,

# to try to detect another stand number

# First, we prepare the ranges around which we'll loop, and make sure

# we're not out of bounds

xMinus1 = max(pixel[0] - 1, minXRange)

xPlus1 = min(pixel[0] + 1, maxXRange)

yMinus1 = max(pixel[1] - 1, minYRange)

yPlus1 = min(pixel[1] + 1, maxYRange)

# Now, we loop to find values

for x in [xMinus1, pixel[0], xPlus1]:

for y in [yMinus1, pixel[1], yPlus1]:

listOfStandsAroundPixel.append(standRasterDataAll[(x, y)])

uniqueNeighbouringStands = set(listOfStandsAroundPixel)

# We remove mentions of the present stand and of the value 0

uniqueNeighbouringStands.discard(standID)

uniqueNeighbouringStands.discard(0)

listOfNeighbouringStands.extend(list(uniqueNeighbouringStands))

# We add the resulting unique standID that we found as neighbors to this stand

standNeighboursDict[standID] = set(listOfNeighbouringStands)

return(standNeighboursDict)- A function to propagate the cuts from stand to stand until we reach a certain size

def standHarvestPropagation(standID,

prescription,

prescriptionParameters,

standNeighboursDict,

standCoordinatesDict,

standAgeDict):

"""

Propagate a harvest prescription from a stand to the neigbouring stands,

depending on the selection criteria + min/max harvest size for the

prescription.

Returns a list of harvested stands.

"""

listOfHarvestedStands = list()

frontier = [standID]

surfaceHarvested = 0

while surfaceHarvested < prescriptionParameters[prescription]["HarvestPropagation"][1] and len(frontier) > 0:

focusStand = frontier.pop(0)

# If we overeach the maximum surface, we stop here.

if surfaceHarvested + len(standCoordinatesDict[focusStand]) > prescriptionParameters[prescription]["HarvestPropagation"][1]:

break

else:

listOfHarvestedStands.append(focusStand)

# TO UPDATE : Surface harvested here is dealt in pixels. But in harvest parameter

# file, might be in different units than pixel. See how to adapt to that. Need cell length ?

surfaceHarvested += len(standCoordinatesDict[standID])

for neighbor in standNeighboursDict[focusStand] :

if neighbor not in listOfHarvestedStands and standAgeDict[neighbor] > prescriptionParameters[prescription]["MinimumStandAge"] and standAgeDict[neighbor] < prescriptionParameters[prescription]["MaximumStandAge"]:

frontier.append(neighbor)

return(listOfHarvestedStands)I won’t discuss all of the functions that are in the template, but there are a lot of them !

So as you see, the first section of this template contains a lot of functions. Many of them actually replace functions that are inside B. Harvest; reading the position of the stands, their age, etc. Again, the trade-off is that here, we have the freedom to do anything we want, but have to re-do it from A to Z. It’s like we’re writing an entire new model in our script. And that’s why these functions are here. The good news is : you won’t have to worry about them one bit ! They’re already ready. So a big, big chunk of the work is already done for you.

Another cool thing : it’s very easy to test these functions, to understand them or to create news ones ! Python is an intepreted langage like R, so you can run commands and interact with it easily. So, you can put your script in a folder containing LANDIS-II inputs and outputs, and you can try it out and see if it works line by line. This makes creating your algorithm and debugging it VASTLY easier than working in C#. In fact, you’ll see in the template a little section that allow you to run the script in “debug mode”.

#%% DEBUG

# Just put "False" unless you're tinkering with this script.

debug = False

# debug = True

# If debugging, we prepare a dummy situation

if debug:

os.chdir(r"path/to/your/folder/with/simulation/files/landis-ii")

timestep = 15

BAU_Modifier = 1

disableTQDM = False

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

else:

# If not debugging, this Python script is normally called in a command prompt by specifying

# some arguments, like the location of the folders containing the files that

# we need relative to the LANDIS-II scenario file

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Remember : argument at index 0 contains the program name.

# The arguments that we want come after

timestep = sys.argv[1]

timestep = int(timestep)

# You can retrieve other arguments here; just use sys.argv[2], sys.argv[3], etc.

# We disable the progress bars of TQDM to not display them in the LANDIS log

disableTQDM = TrueIf not in debug mode, you’ll see (see code snippet above) that the script will attempt to gather “arguments” that were given with the command; here, I’m taking the {timestep} argument i’ve passed through the Magic Harvest Parameter text file from earlier (which Magic Harvest will transform into the LANDIS-II time step at which the script is launched). This way, I have a variable in my script that contains the current time step. There are other ways to get the current time step - for example, by looking at LANDIS-II output files - but this one is the simplest and most reliable in my opinion.

Using functions to read the state of the landscape¶

The second section of the script is then using the functions we’ve just looked at to read files and load the informations of the landscape into Python variables, especially Python dictionnaries.

#%% DEFINING PARAMETERS FOR EACH PRESCRIPTION

# We read the template harvest parameter file, which also contains the parameters needed

# for magic harvest

prescriptionParameters, timestepLength = harvestParameterFileParser("./input/disturbances/harvesting/harvest_BAU_v2.0_TEMPLATE.txt")

#%% READING DATA FOR TIME STEP

# Reading files for stand coordinates

standRasterData = getRasterData("../../sharedRasters/stands_v2.0.tif")

standCoordinatesDict = readingStandsCoordinates(standRasterData,

disableTQDM)

# Reading raster of Management units (UAs)

standUADict = readingStandManagementUnit("../../sharedRasters/stands_v2.0.tif",

"../../sharedRasters/rasterUAInterpolated.tif",

disableTQDM)

# Reading JSON files for repeated prescriptions

repeatPrescriptionPath = "./input/disturbances/harvesting/temp/repeatedPrescriptions.pickle"

if os.path.exists("repeatPrescriptionPath"):

with open(repeatPrescriptionPath) as repeatedPrescriptionFile:

pickle.load(repeatPrescriptionsDict, repeatedPrescriptionFile)

else:

repeatPrescriptionsDict = "noRepeatsForNow"

# Reading vegetation communities

standCompositionDict = readCommunitiesComplete("./community-input-file-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".csv",

"./output-community-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".img",

standCoordinatesDict,

disableTQDM)

# Reading stand ages

standAgeDict = readingStandsAges("../../sharedRasters/stands_v2.0.tif",

"./output/cohort-stats/",

timestep,

timestepLength,

disableTQDM)

# Determining forest types

forestTypesStandsDict = DetermineForestTypesOfStands(standCompositionDict,

standCoordinatesDict,

disableTQDM)

# Determining management unit for each stand (used for the conversion of

# raw to net merchantable volume harvested)

# stand neighbors dict (used for stand propagation)

standNeighboursDict = readingStandsNeighbors(standRasterData,

standCoordinatesDict,

disableTQDM)You might notice that one of these parts deals with repeated prescriptions. So in B. Harvest, you can have prescription that will periodically come back to a given stand - like long-term uneven-aged management or partial cuts -, or come from a second final cut - like the shelterwood method. Again, B. Harvest deals with all through the internal variables of LANDIS-II, in the RAM of the computer. However, the Python script that we run at every time step with Magic Harvest doesn’t have a permanent memory; when the script will finish for a given timestep, it will unload its variables. So, if you want to keep information saved for your script to re-load it at the next time step - for example, the list of stands that have repeated prescriptions so that you know which one to re-harvest periodically in the future - , you’ll have to save this in a file.

Python makes that easy, with many choices : you can export Python objects - like Python dictionnaries - into a .json file, which is a popular format that is human-readable - meaning that you can open the file and read it yourself. You can also save it in “Pickle” format, which is not human readable, but which is made to save and load python objects easily. I recommand the pickle format for complex objects, and the Json format for simpler ones.

Here is the code used later in the script (in the section where outputs are done) :

# We save the pickle file with the data for the next repeated harvests

# Wanted to use JSON, but doesn't work well with the complex dictionnaries I use.

# WARNING : pickle is not human-readable. It is made to be read by a Python script.

if repeatPrescriptionsDict!= "noRepeatsForNow":

with open('./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/repeatedPrescriptions.pickle', "wb+") as outfile:

pickle.dump(repeatPrescriptionsDict, outfile)You can see that there are also a couple of lines to remove the files made by the Biomass Community extension, and which contain all of the vegetation data at the end of the previous timestep (and so, if Magic Harvest is the first disturbance extension to run, it’s also the state of the current time step before anything happens). These files are very heavy, so you might want to remove them once you’re done reading them.

# Removing vegetation communities files if needed

if not debug and removeCommunitiesFiles:

if os.path.exists("./output-community-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".img"):

os.remove("./output-community-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".img")

if os.path.exists("./community-input-file-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".csv"):

os.remove("./community-input-file-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".csv")

if os.path.exists(("./community-input-file-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".csv")[0:-3] + "txt"):

os.remove(("./community-input-file-" + str(timestep- timestepLength) + ".csv")[0:-3] + "txt")You can also see that there is a line preparing a two dimensional numpy array with the same dimensions as the management area map, but filled with zeroes. This is the array we will fill with the location of the pixels we want to harvest precisely, and that we will use to create the management raster that we will feedback to B. Harvest to control its harvesting, as I explained before.

#%% PREPARING OTHER OBJECTS WE NEED

# We prepare the empty management map that we will fill with the values of the pixels where we want to harvest.

managementMap = np.zeros_like(getRasterData("../../sharedRasters/stands_v2.0.tif"))Making the management decisions¶

Now that everything is loaded, this is the part where you can do your management decisions. Here, as this script is a template, this part is empty. We’re going to do some exercises together afterward to explore what we can do here. But sky’s the limit. The only thing we have to do is to fill the array that will be used to output our management map, where each pixel contains the code of the prescription we want to apply in this pixel. The rest is up to our imagination.

#%% MAKING THE HARVEST DECISIONS

# This is where you should write functions that will define where you want to harvest.

# So, doing your repeated prescriptions, ranking the stands and then applying new prescriptions until you

# reach a given target, etc., etc.

Creating the outputs to control Biomass Harvest and others¶

The final section is simply the creation of the outputs. We create an object containing information about the repeated prescription for the next; we create the raster map to give to B. Harvest to control its harvesting using the array we filled before; and we then edit the parameter text file of B. Harvest to add new prescriptions if we want to, indicate the name of this new management map we’re giving him, and also to write the implementation table to force him to harvest 100% of each pixel codes we have put in the map, as I’ve described before. The template also writes a couple of log files to help reading what happenned after the simulation.

#%% OUTPUTS

# This is where we create the files that we will give back to Biomass Harvest

print("Creating outputs...")

# We prepare the folder with temporary files

if not os.path.exists("./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/"):

os.mkdir("./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/")

# We save the pickle file with the data for the next repeated harvests

# Wanted to use JSON, but doesn't work well with the complex dictionnaries I use.

# WARNING : pickle is not human-readable. It is made to be read by a Python script.

if repeatPrescriptionsDict!= "noRepeatsForNow":

with open('./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/repeatedPrescriptions.pickle', "wb+") as outfile:

pickle.dump(repeatPrescriptionsDict, outfile)

# Create harvest maps

print("Magic harvest Python script : WRITING PRESCRIPTION MAP")

writeNewRasterData(managementMap,

"../../sharedRasters/stands_v2.0.tif",

"./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/prescriptions-" + str(timestep) + ".tif")

# Create harvest txt file

# We add to the txt file :

# - The new plantation prescriptions

# - The surface to harvest for each prescription ID / fake management areas to contrain harvesting

writeHarvestParameterFile(managementMap,

"/input/disturbances/harvesting/",

"harvest_BAU_v2.0_TEMPLATE.txt",

"harvest_BAU_v2.0.txt",

prescriptionParameters,

"./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/prescriptions-" + str(timestep) + ".tif",

timestep)

# Update table that gives the prescription names for each prescription ID

# for easy identification in GIS softwares of the harvest output maps

WriteTableOfPrescriptionsID("./input/disturbances/harvesting/tempMagicHarvest/prescriptionIDTable-" + str(timestep) + ".csv",

prescriptionParameters)

# We make a log of the harvested surfaces and volumes.

csvFileOutputPath = "./output/magicHarvest/logMagicHarvest.csv"

# If first timestep, we create the file.

if timestep == timestepLength:

if os.path.exists(csvFileOutputPath):

os.remove(csvFileOutputPath)

# We make the output directories if they don't already exist

if not os.path.exists(os.path.dirname(csvFileOutputPath)):

os.makedirs(os.path.dirname(csvFileOutputPath))

listOfHeaders = ["Timestep", "Surface Harvested"]

for target in volumeTargetDicts:

listOfHeaders.append("Volume " + str(target) + " harvested")

with open(csvFileOutputPath, 'w+', newline='') as file:

writer = csv.writer(file)

writer.writerow(listOfHeaders)

# Then, we write the values

newRow = [str(timestep), str(np.count_nonzero(managementMap))]

for target in volumeTargetDicts:

newRow.append(str(volumeTargetCounterDict[target]))

with open(csvFileOutputPath, 'a', newline='') as file:

writer = csv.writer(file)

writer.writerow(newRow)And that’s it ! Once the script is over, Magic Harvest will force B. Harvest to re-load its parameters, and B. Harvest will then activate and harvest the pixels in the way we told him.

Of course, there are many functions that you could add to the template; for example, functions to read the rasters from other disturbances extensions (like fire and insect epidemics) to then know where to do salvage logging. Don’t feel restricted by what I’ve described here. In fact, we’re now going to finish by making you use your imagination a bit !

Conclusion about using Magic Harvest in practice¶

You should now have a pretty good idea of how using Magic Harvest works in term of using files; or at least inspiration to do your own script and run them in LANDIS-II.

We’re going to finish by doing a couple of exercises to train your imagination to write some algorithms to make your management decisions through a script.